January 28, 2026

By Andrea Friederici Ross

Chicago in the 1880s grew faster than an overfed piglet. A seemingly endless daily roundabout of steamboats, carriages, and railroads brought goods, food, and new residents to help shape a city that had been wiped out in 1871’s catastrophic fire.

It was the fastest growing city in the world, a manufacturing mecca, a crucial hub of distribution in the relatively new Northwest, and a chaotic mess. Melusina Fay Peirce, an 1878 arrival accustomed to the more decorous rhythms of Cambridge, Massachusetts, described Chicago as “an enormous cabbage which might at any time turn into an equally enormous rose.”

Much has been written about the agricultural implements, meat-packing, steel, and other business enterprises that made Chicago a vital city. Perhaps less well known is the social evolution that took place alongside. Peirce’s brother, Norman Fay, drawn to the city by a job with the new telephonic exchange, summed up the environment: “Chicago is a sort of social forge, where things moral, economical, and political get ‘all het up’ as they say in Vermont, fuse together, are hammered out, and cool off in new and generally better form. There is always something doing in Chicago. Parties and politicians come and go, ‘isms and ‘ocracies wax and wane:…sinister figures of bomb-thrower, demagogue, slugger, grafter, frenzied financier, one after the other stalk, menace, fight the town, lose, and fade away; while it grows always greater and more free.”

Five of the seven Fay siblings – Melusina (Zina), Norman, Amy, Rose, and Lily – chose to live on the newly developed north side, where dry goods merchant Potter Palmer had filled in the swampy areas north of the river and built what we know today as the Gold Coast. After a few years in the telephone business, Norman, always interested in the latest inventions, moved on to arc lighting, and then to the typewriter. New ideas were the name of the day.

Social clubs were a vital component of the community. Norman, in a report back to his Harvard alumni association, declared that “Chicago is clubbed to death.” But he was an enthusiastic member of several, including the Union League Club, Union Club, Chicago Club, and University Club. These connections proved vital when Norman solicited guarantors to help establish a new resident orchestra, under the baton of conductor Theodore Thomas. On a Commercial Club train outing to view the new Fort Sheridan army base, Norman worked the aisle gathering signatures for financial pledges.

The Fay sisters had their own club connections, and these not only helped them, and other ladies, break out of the domestic sphere in which women had been confined for decades, but also helped provide avenues for improvement. All were involved to some extent with The Fortnightly of Chicago, a women’s club that provided regular lectures and social gatherings.

But it was music where the Fay sisters made the biggest impact. Middle sister Amy, a concert pianist, back from several years studying in Germany with Franz Liszt and other notable teachers, was active in the Amateur Musical Club and the Artists’ Concert Club. These clubs provided female musicians with performance opportunities that aided their music careers at a time when critics and conductors were hesitant to welcome women into the field.

Younger sister Rose became president of the Amateur Musical Club and utilized the 1893 Columbian Exposition to gather representatives from other music clubs around the country, an effort that ultimately led to the founding of the National Federation of Music Clubs, a non-profit organization still operating today. Rose’s marriage to Theodore Thomas positioned the pair as a musical power couple, with her club helping promote concerts of the new Chicago Orchestra, and the conductor’s support boosting the women’s efforts in music education. Rose also utilized her social connections to establish the Anti-Cruelty Society, a volunteer organization that advocated for improved conditions for carriage horses and domestic animals, and even for abused women and children.

Whereas businesses can tout financial figures for growth and cite statistics to demonstrate their impact on society, the work of clubs, and, often, women in history, can be harder to quantify. But the social connections forged and the management skills learned in these groups helped effect change and ultimately pave the way for the women’s vote and for the activities of the Progressive era.

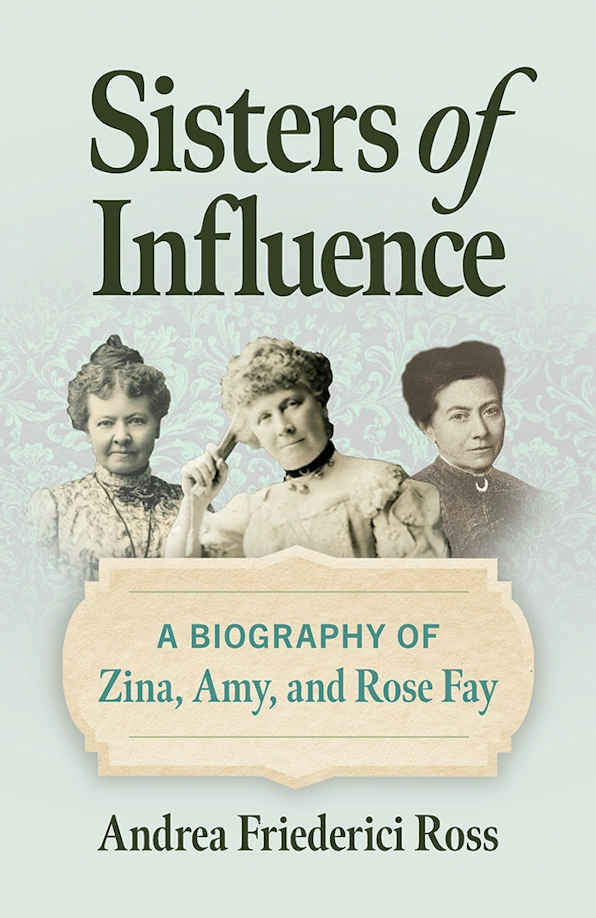

Andrea Friederici Ross is the author of Edith: The Rogue Rockefeller McCormick and Let the Lions Roar! The Evolution of Brookfield Zoo. She has worked as the operations manager of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, assistant to the director of the Chicago Zoological Society, and at her local public school library. Sisters of Influence is now available from Southern Illinois University Press.